This was arguably the most unusual spring and summer as I had not traveled outside the Baltics for more than five months and could finally not be missing out on local events. The art life in the Baltics quickly restarted after a short halt in spring, following a general easing of lockdowns, adaptation to the new rules and promisingly low COVID-19 rates. Museums and exhibitions were considered the safest places out of all the cultural venues considering the possibility to distance oneself from others, apart from at exhibition openings, of course. The end of summer and early September came with an abundance of long-prepared and postponed events colliding with those that were planned to happen at that time anyway, intensifying the art calendar. In this text I would like to delve into several of the events I experienced and, through them, look at the important issues currently addressed in the Baltics, like different attitudes and manifestations through art related to questions of nationalism, race and gender.

The first exhibition opening “abroad” I attended after the start of the pandemic was Olev Subbi: Landscapes from the End of Times curated by Catalan curator Angels Miralda at the Tallinn Art Hall. It was the end of July and I remember my hesitation at first as I had so much fallen out of the habit of travelling, and terms of safety and protection had interwoven the vocabulary and changed significantly the actual reality of mobility. However, a spontaneous decision followed, and, in a few days, I already found myself on the bus from Riga to Tallinn. After all, we had already experienced the unseen flows of regional tourism from mid-May when Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania opened their common borders, creating the first “travel bubble” within the European Union aiming to jump-start economies broken down by the coronavirus pandemic. 1

The exhibition was re-examining the practice of the well-known Soviet Estonian painter Olev Subbi (1930–2013) offering a new perspective on his practice alongside the work of contemporary international artists adding discourses that diversify and subtly challenge his attitudes towards gender and ecology. The idea of the landscape was important to Subbi as a place of hope and memory, a site of escape, too, as during the Soviet times he often returned in his work to the 1930s as a lost utopia of independent Estonia. Within the exhibition it also became a site to construct the potential for more inclusive and equal futures for everyone. Juxtapositions between Subbi’s work and contemporary artists were key to this exhibition. For example, in one of the rooms, his female nudes, which were celebrated during Soviet times as they opened up a place for sexual desire in the rather conservative public life, however, they are now looked at as objectifying women, were placed in the same room as the work by artist Nona Inescu. Her installation comprises a metal structure enclosing stones laid out on the floor in supple tree shape (Meander, 2020) and the video Vestigial Structures (2018). The video juxtaposes black-and-white scenes of the mythical stone formations in Carnac, Brittany superimposed by images of a queer body doing exercises with stones, some of which are attached to the body like bone outgrowths. The female nudes by Subbi are almost encouraged by the queer bodies from the video, to fight for the right over how they are represented creating an empowering alliance over time and space.

Just a week before another poignant exhibition had opened at the same venue, Narrating Against the Grain with new commissions by Alina Bliumis and Tanja Muravskaja, curated by Corina Apostol. It took Edward Said’s observation in Culture and Imperialism (1993) that “Nations themselves are narrations,” a statement that holds especially true in our current time when nationalism and populism are on the rise, and expanded it into a presentation of photographs, interviews with vulnerable members of society about life during the pandemic, as well as a series of banners emblazoned with different types of big cats from national passport covers. Even through the windows one could not help but notice the numerous repeating photographs of women in burkas, each one forming the black line on the background of the white and blue of the Estonian flag. Their author, artist Tanja Muravskaja lives in Tallinn and has Ukrainian roots, and the themes she addresses are often connected to nationalism in Estonia amplifying the voice of the ethnically marginalized groups of society.

Discussions about nationalism, ethnicity and race were also reactivated in the other Baltic countries this summer as a reaction to the Black Lives Matter protests in the US following the police killing of George Floyd. According to sociologic research in Latvia, only about 20% or one in five Latvians would have no objections if their colleague, family member or neighbor was of another nationality or origin. 2 Discrimination operates through manifold places, including apartment and job markets, as well as hate crimes. In Lithuania, curator at CAC Vilnius Virginija Januškevičiūte and artist and curator Gerda Paliušytė have been working since 2019 on the project Race Conversation, a series of film screenings and events organized to ask: How is the issue of race reflected in Lithuania? With this among other important questions the project aims to address the question of race locally. It is not a common topic in either of the countries and is often considered an American import as the Baltics are racially almost homogenous, but the people of color are regarded as immigrants and refugees or connected to experiences of travel. 3

As a practical and discursive reaction at the same time to the BLM protests, Lithuanian curators, activists, and artists made a glossary in Lithuanian to address the issue of race and racism in the Lithuanian language, an initiative all the Baltic countries should follow to vocalize and help the discussion about race to enter the collective awareness of our societies.

The issues of nationalism and colonialism in Latvia were also recently addressed at the International Summer School, curated by Ieva Astahovska and Andra Silapētere from the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art. The school aimed to analyze the legacies of post-socialism and postcolonialism through a gender studies perspective. It took place in Kuldīga, now a postcard town, but was once – in the late 16th, 17th and 18th centuries – a rapidly growing center of the Duchy of Courland. The 17th century was also the time when the Duchy had colonies in Gambia and Tobago for a short time, and was even involved in the slave trade – international trading relations that brought prosperity to the province. The fact that a territory that is part of present-day Latvia – Courland – once held colonies is still often mentioned with national pride and without any critical assessment and often appears through books, films, plays and place names. Within the summer school the artists Quinsy Gario and Jörgen Gario addressed this issue in the performance How to See the Spots of the Leopard in the public space next to the monument which was erected to the Duke of Courland just recently, in 2013. In the performance the artists connected reflection on their Dutch Caribbean heritage and Latvia’s connection to European colonialism. The artists are from the island of St. Maarten, where Duke Jacob Kettler’s ship The Hope was spotted in July 1645 transporting ivory and pepper from present-day Liberia to the Caribbean. From there it took tropical timber to Europe. Mixing spoken word with steelpan music, a musical form invented on Tobago, and playing on the Latvian traditional instrument the “kokle”, they evoked the sleeping collective memory of the colonial times. Quinsy Gario would endlessly repeat the question “Are you nostalgic?” to the public and count a myriad of issues one could be nostalgic towards – from timber, to open oceans and seas, to adventure and other elements traditionally linked to colonialism, and specifically to this particular case.

National politics are also coming to the fore in the wake of the global pandemic which has highlighted the incapability of countries and regions to address the health crisis together. However, on the international scene the usually marginal and simply less dense Baltic capitals suddenly felt like a center of international art life, as over the summer they proved to be more comfortable, habitable and safe environments. International visitors, missing the postponed art exhibitions kept coming to Riga where things had already opened.

One of the international magnets was the second edition of the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art curated by Rebecca Lamarche Vadel. It was supposed to open on May 2020 but due to COVID-19 was postponed to August as a physical exhibition open for three weeks and a film being shot during the exhibition time. It took place in the former port district of Andrejsala in Riga, a place where local political and economic interests have collided for years over the deep-rooted ownership of the port by the local oligarchy which, as well as mismanagement from the state, has blocked sustainable development of the place. Here, more than ten years ago a plan to build the Contemporary Art Museum of Latvia, in a Rem Koolhaas projected building, failed due to complex ownership issues. Currently, part of the area has been taken over by non-human animals and plants and going to the exhibition felt like an expedition.

I valued the honesty of the curator when at the opening press conference, she said that COVID has been her main co-curator shaping the project, making her and the artists rethink the works and the exhibition. It appeared in subtle notes, like through the wall markers left on the floor where no walls were finally built as there were fewer artworks and a decision was made to leave the space more open and borderless. The catalogue also held the old information on how things should have been, which was visibly crossed out while new information was added, for instance, the change from a live performance to a video work.

The impression the exhibition conveys is a subtle oscillation between heightening the sense of the end of the world to evoking hope, as the end of the world usually just means the end of the world for humans. The dogs are allowed into the show and stray cats can have milk from the piece by Nina Beier (Total Loss, 2020), which is poured regularly in the folds of her marble lion sculptures. In the overgrown former paintball field young Lithuanian artist Anastasia Sosunova created Habitaball (2020), adding minor site-specific sculptural interventions to the powerful outdoor space, telling the story of a fictional gaming community that used to inhabit the place. Estonian artist Jaanus Samma in his work Riga Postcards (2020) has researched the diaries of Kaspars Irbe (1906–1996), full of meticulous documentation of the queer subculture through the Soviet times. Referring to the original material, Samma created an installation of postcards as if advertising Riga as a gay travel destination in the 1970s–1980s. Even though homosexuality was criminalized in the Soviet Union, Riga was a destination for gay men from neighboring countries for work, sightseeing and casual sexual encounters. These are but few of the thought-provoking artworks revealing local and international stories entangled in different paths of worldmaking.

A few weeks later the 11th contemporary art festival Survival Kit opened, curated by Katia Krupennikova, titled Being Safe is Scary. It was not directly affected by the pandemic, as it opened at the planned time, however, the theme touching upon safety and fear gained a completely different meaning over the course of the year of preparation of the festival. The festival is trying to point out the connection between state practiced security measures and the violence and exclusion vulnerable groups often experience because of their race, ethnicity or sexual identity. It also points to the idea that notions like safety and security should be reconnected to practices of love and care, thus creating a more inclusive society for everyone.

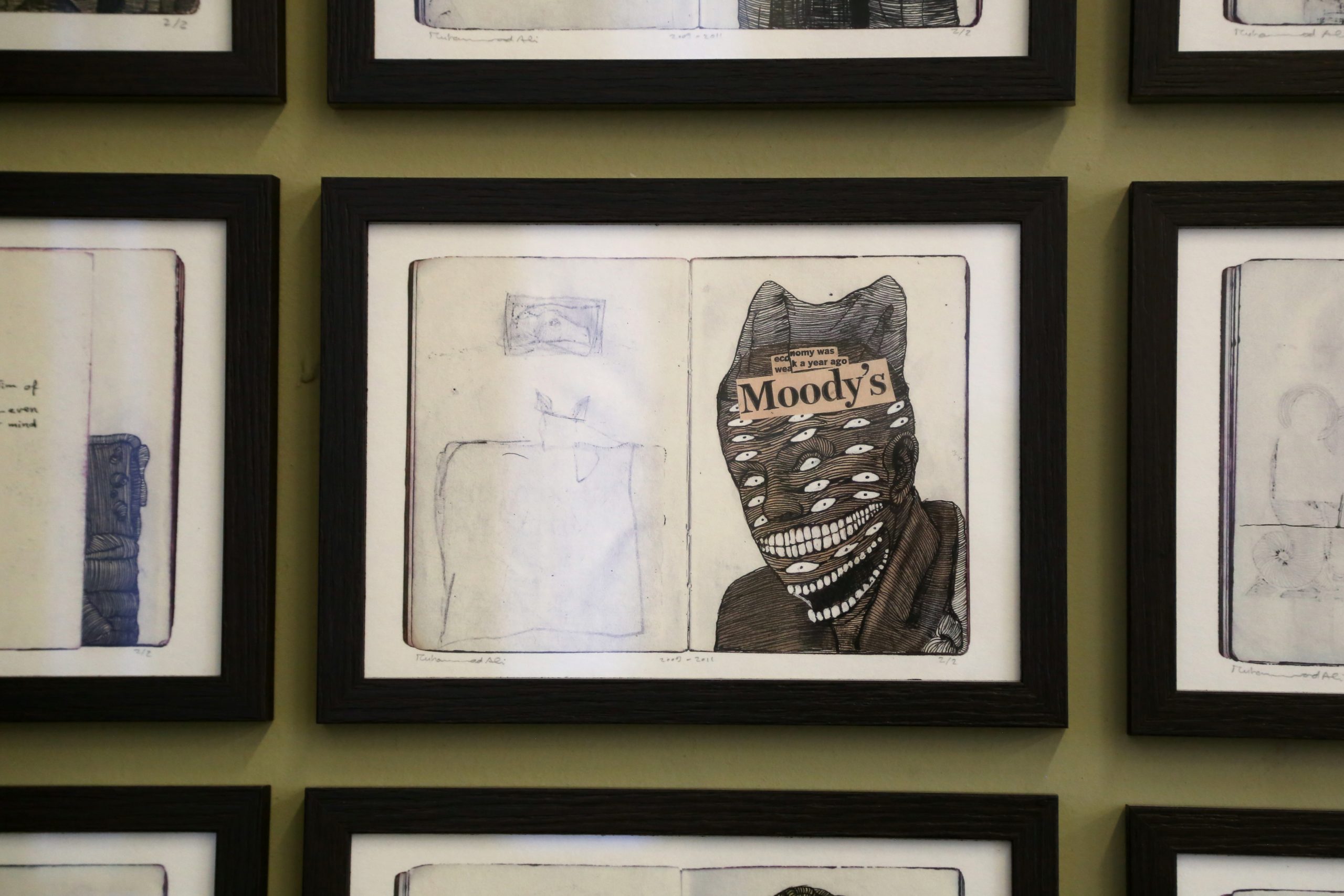

In one of the most poignant works, the Syrian-born Swedish artist Muhammad Ali, through his small series of drawings I Am Just a Number, refers to his experience of being rendered invisible in Sweden during his immigration process since he was given a number while losing everything else from friends and family to professional life and status in society. His personal story helps to unpack the hidden ignorance and violence of the state practices. The Latvian artist Līga Spunde in her video installation, refers to other types of individual fears that evoke larger societal issues. Citing the famous story of the Bubble Boy, a well-known sufferer of severe combined immunodeficiency which dramatically weakens the immune system she also questions our limits and possibilities of saving the most vulnerable members of society, which is another issue that the pandemic has just heightened. In her work, the bubble becomes a poetic metaphor since it is as safe as it is fragile.