Mushroom hunting is a common practice among those living in the regions of central and eastern Europe. In the Czech Republic about 70% of the population visit forests for mushroom foraging and one household can gather almost 11kg of mushrooms per year1. This adds Czechia to a group of mycophilic societies, i.e., societies which hold mushrooms in high esteem. This is in distinction to mycophobic societies—such as the UK—where mushrooms are little known and feared. The distinction of mycophilia and mycophobia was proposed by the Russian-born doctor and a US emigree Valentina Pavlovna Wasson. Valentina and her husband Gordon Wasson are nowadays considered the founders of ethnomycology, a science that examines the historical uses and socio-cultural impact of fungi.

We, the authors of this article, had very different paths toward fungi. Being from the Czech Republic, Lenka has been immersed in mycophilia from childhood. Her grandmother Jana Divišová would take her foraging and teach her the most important things about fungi—how to find them, how to identify, pick, process and preserve them. Like her grandmother, Lenka gets easily lost in the woods in the heat of a mushroom hunt and eagerly recounts her mushroom foraging adventures. Oftentimes these stories get an overtly sentimental flavour, since they also carry longings of all sorts, particularly for one’s childhood or homeland. Elspeth grew up in a city in the south of England. The only mushrooms Elspeth properly noticed, smelled and tasted were button field mushrooms wrapped in plastic on the supermarket shelf. She discovered mushroom foraging while living in Finland in 2016 and caught what feminist anthropologists have called ‘mushroom fever’. She was astounded by the lack of knowledge of fungi in her own community and so, when visiting her mum for example, she is the one guiding and advising her on species and edibility. Still, within this mycophobic culture, her mother is not yet confident enough to try the Chantarelles (catharellus cibarius) or Penny Buns (boletus edulis) they have found on their walks in the woods together.

As these recollections suggest, our relationship to fungi is primarily practical, situated, relational and affective. Together, we combine the sensibilities of exploring the strange biology and cultures of fungi and mushroom foraging with our feminisms. For us, this combination illuminates a path through which we interrogate and pull apart socio-cultural phenomena where extreme binary polarisations (such as native vs. alien) have become an underlying logic. This includes the logic that reproduces xenophobic and racist nationalisms, gendered and sexual violence, and environmental destruction.

Ethnomycologists explain the disparity in cultural attitudes towards fungi (mycophillia and mycophobia) as a combination of their strange biology and ecology, their huge biodiversity, and the lack of knowledge modern science has about these organisms. Furthermore, in recent years, countries that have traditionally been mycophobic, like the USA and UK, have experienced a shift in attitudes towards fungi, becoming mycophilic. It is not insignificant that these countries also still occupy a hegemonic position within the global economics, politics, culture and the production of knowledge. Thus, the mycelium and its (often anglophone) metaphors have been growing through the worlds of techno-science, economy, ecology, politics, philosophy, arts and popular culture, also creating new and intricate entanglements among them. Within academia, this even led some scholars to announce yet another major and newest turn within Western thought, the ‘mycological turn’.

Our work is resourced by this turn and makes its intervention by examining the traces fungi and their metaphors leave in the political and aesthetic re-articulations of nationhood, race, gender, sexuality and the human and non-human relations. It also asks what can we learn from mushroom foraging as a situated, relational, material, and affective practice? And what can encounters with fungi do beyond the ecology of the forest? Our inquiry draws on a methodology developed by feminist anthropologist Anna Tsing. Tsing complicates the fixed and polarized horizons of utopia and apocalypse that define the dominant discourses on socio-economic precarity in the face of environmental destruction, and thus seeks to provide means of resistance to their feral effects.2 Mobilizing Tsing’s approach, and learning from the fungal biologies and ecologies themselves, we understand mycophobia and mycophillia not as exclusive binaries that define all societies but as entangled, situated and mutually constitutive cultural positions. We deploy this as an analytic to study embodiment and belonging with the hope that it may help us see not just the successful working of coloniality, heteropatriarchy, racial capitalism and anthropocentrism, but also the signs of resistance to these global systems of power.

From Fungal Narratives to Mycorrhizal Encounters

Fungi are captivating and charismatic organisms. Many mycologists, activists, entrepreneurs, healers and scholars believe that fungi can provide solutions to multiple problems, from cancer to climate change. For example, myco-architecture made from mycelium (the part of the fungus consisting of branching threadlike hyphae underground) is being tested out by NASA for the construction of future homes on the Moon and Mars. The wellness and pharmaceutical industries suggest that mushrooms can be used as a prebiotic and heal human bodies and souls in multiple ways. Research into psilocybin continues to show promise to treatment of anxiety and depression. British clothes designer Stella McCartney sells garments made from lab grown mushroom leather trademarked as ‘Mylo’. Quorn, the popular vegetarian and vegan meat alternative is a mycoprotein. The slime mould Physarum polycephalum that has traditionally been used as a model organism in cell biological, biochemical and genetic research, has recently been put to work to also recreate layouts of various systems such as Tokyo’s rail network or motorways in the USA. However, in a more explicitly sinister manner, it was used to predict patterns of migration from Mexico to USA. It has also been suggested that mycoremediation, a process that harnesses fungi’s abilities to break down materials, can be an economical and eco-friendly way to combat soil and water pollution. Finally, mushrooms are, of course, also a delicious delicacy and staple food item in many cultures.

In addition to these examples, fungi are also remarkably good at carrying or absorbing ideas and stories – they capture our imagination. One of the metaphors that currently dominates the field of fungal imaginary is that of the de-centralized network. Mycelium is imagined as a kind of pipeline as, for instance, ‘The Wood Wide Web’ that connects trees in the forest, a term coined following the research of Canadian ecologist Susan Simard. Following a similar path, cryptocurrency and blockchain consultants make comparisons between the decentralized structure of bitcoin and the mycelium, whereas the Spore Liberation Front (SLF), which envisions fungi as sentient networked life forms, takes fungi as teachers of radical political action against oppression. James Cameron draws directly from the mycorrhizal fungi’s relations with trees popularised by Simard—and that is not so dissimilar from that of SLF—in his blockbuster film Avatar (2009). In the film, the alien moon Pandora is made a stage on which the history of colonial imperialism is yet again told through the heroic and live-transforming journey of a coloniser. Pandora contains a ‘Hometree’ which, through a biological network, connects all living beings, including the humanoid indigenous tribe Na’vi.

Many other films and television programmes explore the biological and cultural expressions of fungi. The Netflix documentary-series The Goop Lab (2020), which promotes lifestyle and wellness brand and company Goop founded by American actor Gwyneth Paltrow, successfully exploits the connection between fungi, healing and idealised femininity in its first episode ‘The Healing Trip’ that revolves around a psychedelic mushroom ceremony. Films Phantom Thread (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017) and The Beguiled (dir. Sophia Coppola, 2017) both show women using poisonous mushrooms as a weapon to combat so-called toxic masculinity. Mushrooms are mythically powerful, either as a symbol of deep connectivity, for medicinal and spiritual healing, or as harbingers of evil and death.

In European cultures, the association between fungi, decay and death has been around since at least the medieval era. In modern history, this association was infamously mobilized in an antisemitic propaganda children’s picture book Der Giftpilz published by a published Der Stűrmer in Nazi Germany in 1938. The purpose of this picture book was not only to incite fear and hate but also activate engagement in the persecution of Jews, paving the way and explicitly calling for the ‘Final Solution’ in the extermination of Jewish population, a message for which the publication relied on the dehumanisation of Jews through a comparison with poisonous mushrooms. In 2020 Der Giftpilz was published in Czech by Guidemedia, a publisher connected to Czech neo-fascist and neo-Nazi scene. However, as identified in the poem ‘Mushroom Hunters’ by performer, poet and anarchist Milan Kozelka, in Czech Republic, fungi are deployed as a defining feature of national identity also in mainstream political culture. A Facebook post from September 2020 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs describes Czechia as ‘mushroom hunting superpower.’ In the same year, a candidate for election to the senate and ANO Party, MP Karel Reis invoked mushroom hunting in his campaign on social media. Expressing his love for mushroom hunting as well as his family, Reis vowed to fight against the measures that seek to limit and tax mushroom foraging that were apparently being forced on Czechia, presumably by the European Union.

Fungi, however, can be mobilised for negotiating belonging beyond the racialized modern nation-state. In a different manner, these organisms are often used to think about the problems of climate change on a global scale. In 2008, prominent American mycologist and entrepreneur Paul Stamets gave a TED talk entitled ‘6 ways mushrooms can save the world’ that develops some of the insights of his book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World from 2005. Stamets’ work with mycelium, particularly in terms of mycoremediation of ecosystems and mycopesticides, has been hugely influential. His influence even led to a main character being named after him in the recent Star Trek franchise, Star Trek: Discovery, a series which explores a mycelium network as a discrete subspace domain (a mycelial plane of space-time) connecting every part of the multiverse. The character Paul Stamets, played by Anthony Rapp, leads a team who devise a ‘spore drive’ propulsion system by which they can instantly traverse great distances through the network. This astromycotechnology equips the United Federation of Planets to pursue and accomplish its political interests against various enemies, such as the Klingon Empire and the Emerald Chain. What is implied is that to save the interests of the Federation is to save the ‘universe.’ Only certain planets and inhabitants, however, count as belonging to this universe.

The fungal tales of paternalism and colonialism told by Star Trek: Discovery and the above-mentioned Avatar are not dissimilar from the one told in early 1990s blockbusters Dances with Wolves (1990) or The Last of the Mohicans (1992). These two films are identified by academics Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang as inscribing ‘settler’s moves to innocence’, a set of evasions that ‘problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity.’3 The rule of non-intervention in the natural evolution of a species or culture (in case of Star Trek) or the deployment of settler adoption fantasy (Avatar) are mechanisms which facilitate such ‘settler’s moves to innocence.’ In our examples, however, the invocation of mycelial networks scales up this colonial tale to a multi-world, and multi-versal level.

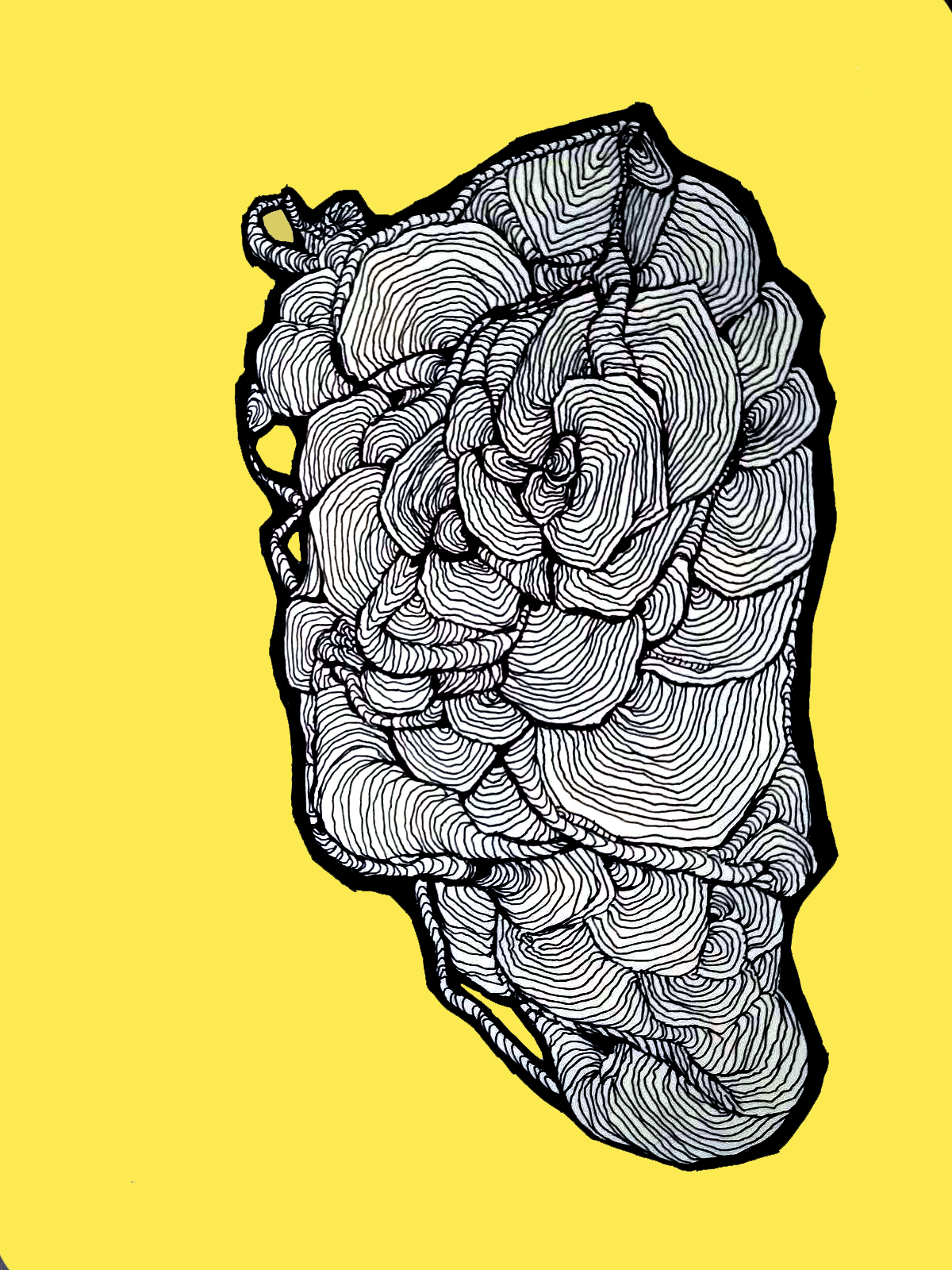

Nevertheless, artistic and cultural practices with fungi do not always fall into this logic. Mycorrhiza describes a mutually beneficial association between a fungus and a plant. Drawing from this relation, in our work we propose a new concept of mycorrhizal encounters. Through self-reflexive relations with fungi, this concept names a feminist decolonising practice that seeks to embody movements different from the moves to innocence described by Tuck and Yang. The dialogic drawing projects by Mexico-based Mestizx artist, activist, educator and scholar Xalli Zúñiga is one example of such practice. Zúñiga’s dialogic drawing projects are partial, situated, embodied and entangled practice-in-motion that are generous, connective and caring in character. They aim toward stimulating a capacity for alternative meaning-production and thus enable self-reconstruction, anti-colonial memory work, and relearning and reattuning to different affective currents. Xalli Zúñiga thus seeks to build coalitions that are key to any efforts for social and environmental justice and liberation under anthropocentric, heteropatriarchal and racist capitalism. For us this kind of work opens onto a possibility of radical transformation through engagement with fungi.

This article draws on a talk given by Lenka Vráblíková at Descendants of Fungi and (Eco-)Politics of Sharing festival organized by Woods – a community for cultivation, theory and art (2021). The talk can be accessed on https://soundcloud.com/user-950559143/potomci-hub-lenka-vrablikova-feministicka-etnomykologie-a-politika-vizualni-kultury?in=user-950559143/sets/potomci-hub-neuroplasticita