In the times of the dominating Socialist Realism, the Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko (1908-1997) managed to create her own unique universes inhabited by fantastic animals and surreal plants. Her oeuvre went beyond any imagination that was conditioned by the time by the strict policy of censorship and repression pursued by the Soviet government.

Maria Prymachenko is an emblematic artist for Ukrainian culture. She represents both folk naivety and rootedness in the tradition and the liberation from the conventions that women experienced in rural Ukraine. In between the hard routine of the Soviet-time kolkhoz-bound village life, she managed to open a window into a variety of new worlds borne by her imagination. Part of her creative freedom was, undoubtedly, in the fact that the artist was seen as a representative of folk visual tradition, marginal from the Soviet official perspective. However, Prymachenko’s artistic innovation is undeniable. Her artistic method was informed by both local folk painting styles – before Prymachenko used predominantly in decorative arts – and a particular dialogue with Ukrainian and European early twentieth-century Modernism and Surrealism.

Born in Bolotnya, Kyiv region, to a peasant background, Prymachenko seemed to be deemed to following the track of millions of Soviet women in rural areas: poor unresourceful living, the obligation to involvement in collective farming, and deprivation of basic human rights, such as the absence of passports for free movement inside the country. However, destiny was both uneasy and favourable to Prymachenko, providing her with rather unusual circumstances for the artist’s professional development and gifting her with a bright and outstanding talent for painting. Her family, though intrinsically linked to rural life, worked with the applied arts. The father of Pymachenko, Oksentyi, produced decorated wooden fences, adorning them with zoomorphic and floral carvings. Her mother, Paraska, was a well-known master of traditional Ukrainian embroidery. The artist suffered from poliomyelitis in her childhood and was exempt from hard work in the field. Due to her disability, she spent most of her time at home, painting and embroidering.

As the fame of the talented twenty-seven-year-old artist working with materials as simple as paper, gouache and watercolours reached Kyiv, in 1936, she was invited to join the Central Experimental Workshops at the Kyiv Museum of Applied Arts. The main aim of these workshops was to prepare for the 1st Republican Exhibition of Folk Art that was slated to take place the same year with the itinerary covering various important cities across the Eastern Bloc. The bright and fresh vision of Prymachenko immediately gained popular attention and she was provided with a separate room to show her works at the exhibition. The next year, her paintings travelled to the International Exhibition in Paris where she was awarded the Golden Award.

Paradoxically, while the year 1937 brought success to Prymachenko, it also marked the culmination of Joseph Stalin’s repressions of Ukrainian artists and intellectuals of the generation known as the “Executed Renaissance.” One prominent example of such repressions, among many, was the execution of the monumental painter Mykhailo Boichuk and his circle, including his wife, collaborators, and students who also aimed to bring Ukrainian folk motives, along with Christian iconography, to Soviet art and the subsequent destruction of most of their works. This case was exemplary of how Stalinist politics attempted to shape “the national question” through art, with the pendulum of the state’s cultural policy swinging to different sides in search of an ideologically acceptable language for a utopian representation of numerous oppressed nations inside the Soviet Union.

Although embraced by the Soviet system of art production, importantly, Prymachenko further into her career never stood aside from political commentary and expressed her strong anti-war and anti-violence views through her art. Her works express the sensitivity with which the artist perceived and interpreted the social situation surrounding her.

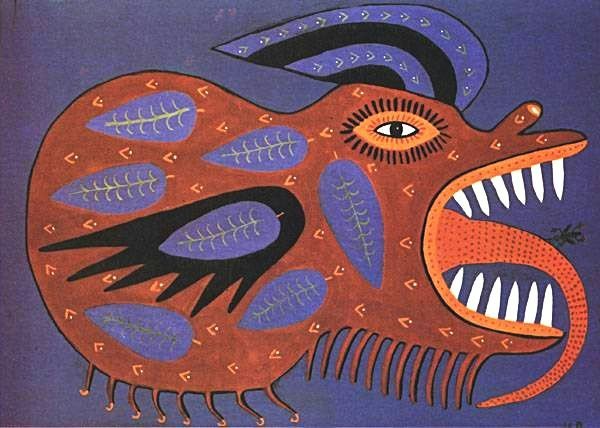

In her 1978 work “May that Nuclear War Be Cursed!”, Prymachenko has no shortage of bright, fluorescent colours to depict a monster of the war with a double snake-like tongue, both threatening and mesmerizing. The artist’s expressive statement reflects the popular fears of the Cold War epoch and the premonition of the end of nuclear détente between the USSR and the United States that began in 1972 and finished in 1979 with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Her work absorbs modern forms and topics into an otherwise folk setting and transforms an abstract image of war and destruction into a zoomorphic shape.

Another work, “The Threat of War” (1986) is instead painted in dark, gloomy colours that depict a missile-looking animal with numerous insect legs and – again – with a long predatory tongue that greedily seeks its victims. The work made in the year of the explosion of the Chornobyl nuclear plant in the vicinity of Prymachenko’s home village attests anxiety of invisible yet real threats of the modern epoch, as well as translates the fears of destruction and violence into a narrative that gives a form and a face to the evil. This artistic method of turning tragic experiences into bestiaries is representative of Prymachenko’s metaphorical thinking and folklore-inspired animistic worldview.

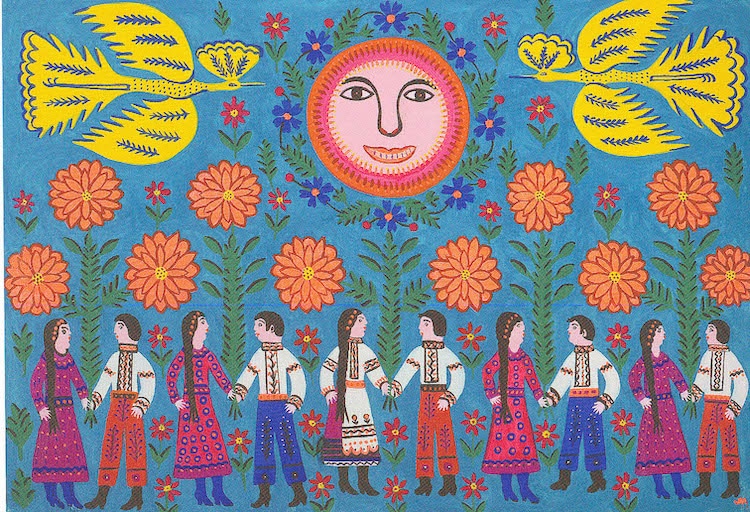

In her other works, the topic of a peaceful sky gains particular importance. The gouache work on paper “Our Army, Our Protectors” (1978) depicts a joyful village celebration, with a sun shining over the village and couples dancing as if celebrating victory. The jolly feast of life is not interrupted by any threat because two large fairy-tale birds protect the peaceful sky over the dancers. This idyllic image once again becomes desirable for the current situation with the Russian invasion in Ukraine, when the sky has lost its safety due to Russian bombs shelling Ukrainian cities, and military aviation became of major importance for reaching the security and lives of the people in Ukraine.

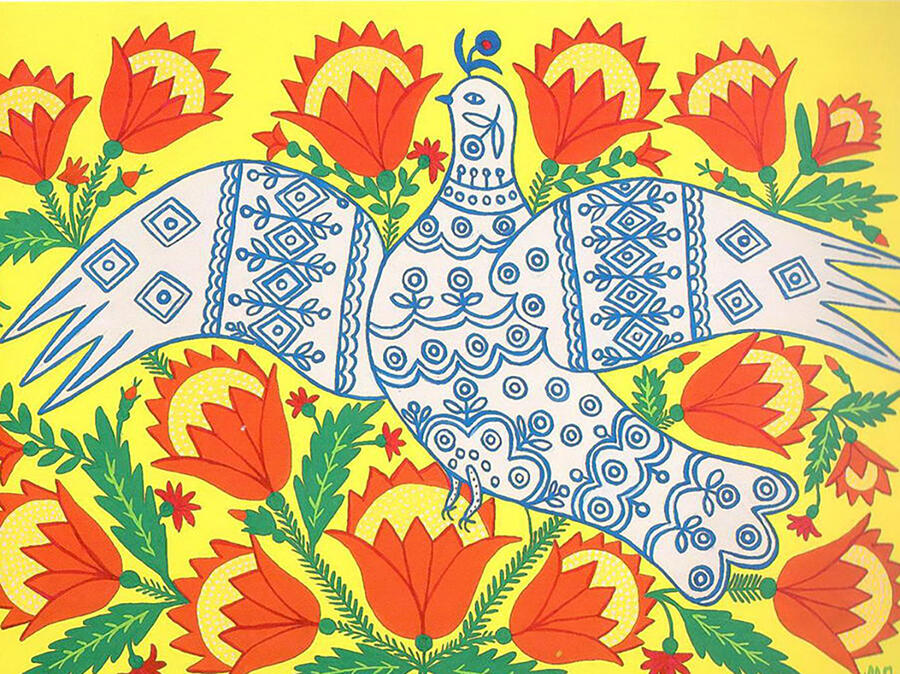

The painting “A Dove Has Spread, Her Wings and Asks for Peace” (1982) depicts a dove of peace covered with elaborate folk motifs. Her protective wings overshadow the soil and flowers growing on it and defend them. The images make a homage to Pablo Picasso, who, in his turn, was reportedly fascinated by Prymachenko’s works that he saw in Paris in 1937. The protective gesture draws on the traditional Ukrainian iconography and folk icons from Prymachenko’s native Ukrainian Polissia (a region in the North of Ukraine), being reminiscent both of the depictions of angels and the Ukrainian icon of “Pokrovy,” where the Virgin protects her followers by spreading her cape over them. These links also mark Prymachenko’s symbolic connection to the artists of the Ukrainian avant-garde of the 1920s, who were also often inspired by Ukrainian village icons, and her indirect references to the Boichukist School.

Prymachenko’s works carry a particular kind of irony that was also expressed in short phrases or verses that the artist wrote herself, taking inspiration from folk oral tradition. The painting “This Beast Has Opened His Mouth and Wants to Eat the Flower, but His Tongue is Thin” (1985) depicts a monster in a military cap who attempts to devour a flower but fails to do so. The weakness of the monster is highlighted by him facing the strength of numerous seemingly vulnerable plants that resist his invasion in their field. The viewer joins the artist in contemplation of this grotesque struggle between the helpless aggressor and the silent yet significant resistance of its victims.

Maria Prymachenko lived a long and artistically fruitful life, witnessing both the ruination of the Russian Empire and the formation of the Soviet Union and its subsequent dissolution and the development of independent Ukraine. She reflected the numerous anxieties and turbulences of the twentieth century in her work but also managed to reinterpret and overcome any apprehension with the seemingly childish visual methods, transforming the difficulties and traumas of everyday living into fairy-tale monsters that do not horrify but rather provoke curiosity, therefore reliving the historical traumas to which she was both spectator and participant.

The uneasy Ukrainian history kept unfolding after the artist’s death and directly affected her heritage. Prymachenko’s home village, Bolotnya, together with the district centre, Ivankiv, was occupied by the Russian troops at the beginning of the current Russian ruthless invasion of Ukraine. In February-March 2022, as the Russian army rapidly proceeded into Ukrainian territory violating its border with Belarus, many buildings in the north of Ukraine were shelled and numerous civilian casualties occurred. On one of the first days of the ongoing invasion of Russia in Ukraine, the Russian troops burnt down the local museum of history and archaeology in Ivankiv. The museum holdings included early-medieval archaeological artefacts, rare Polissia (North Ukrainian and South Belarusian) folk icons and a collection of 25 works by Prymachenko. Further, it was confirmed that her works were saved thanks to the resilience of local people who before the invasion hid the paintings in their houses. This situation shows the threat that both cultural heritage and human lives experience in the ongoing war of Russia against Ukraine, and particularly the threat that collections of regionally important museums face.

At this moment of continuing risk to the national heritage, another work by Prymachenko has made a great contribution to the resistance to the Russian aggression, becoming the key lot in a charitable auction in support of the Ukrainian army and the humanitarian needs of Ukrainian refugees. On 29 April 2022, her painting “Flowers Grew near the Fourth Reactor [of Chornobyl]” (1990) was sold for a record $500 million to an anonymous buyer – who subsequently donated it to the National Art Museum of Ukraine, and in this way, it became the most expensive Ukrainian artwork ever sold. Her other work, “Scarecrow” (1967), has been included in the main project of the latest edition of the Venice Biennial as a last-moment addition that manifested a commendable intention of the curators to support the Ukrainian art scene in a time of war. The description of the work, however, showed the necessity of further international work with decolonization and opposition to Russia’s centuries-long appropriation of Ukrainian cultural achievements, as the label of the painting marked the artist as “born in Bolotnya, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine).” Such a representation of the important Ukrainian artist turns us back to the anti-colonial struggle that is unfolding in Ukraine but also points out a necessity of a more amplified informational campaign about Ukrainian art and artists on the global level, and this article was written to contribute to this mission.

As Ukrainian culture still persists in permanent danger of both colonisation and physical destruction of cultural institutions and artefacts, the current history proves that the anti-war statements touched upon by Prymachenko, continue being very actual, as they respond to the materialised fears of the epoch. The works by Prymachenko exemplify the widespread Ukrainian commitment to peaceful and joyful living in harmony with nature rooted deeply in the traditional culture. In a childish and naïve way, they also reflect on the threats and dangers Ukrainian history faced over the twentieth century and the challenges of its belonging to the Soviet socialist state. The magical worlds created by the artist, however, give a powerful and beautiful way of escape from the uneasy and cruel reality into the domain of imagination and freedom.