Hana Janečková talks to British feminist art historian and writer Katy Deepwell about feminist writing, women’s visibility in the artworld and the art journal, n.paradoxa, that she founded and ran from 1998 until 2018.

Hana Janečková: How did the whole idea of an international feminist art magazine n.paradoxa come along in the late nineties ?

Katy Deepwell: At that time, I was travelling a lot and I had met many women art critics, artists and curators. As I was researching feminist art practices, it wasn’t hard for me to identify the range of people who would be interested in writing about feminist theory in relation to contemporary art produced by women artists. What I decided to do, as an editorial approach, was to make the journal as a permanent research vehicle – without a “stable of regular writers” – and instead endlessly reach out to women in many other parts of the world. I spent a lot of time writing to feminist academics and critics who had written about different women artists or aspects of feminist theory. It’s very old-fashioned but it is also necessary as an approach, to write to people explaining what the journal was as a platform and a space and inviting them to take part.

HJ: Was this then about establishing these personal links, personal relationships…

KD: It was about much more than personal relationships. I ceased to be frightened to write to people whose work I had only read. At the time, people still sent faxes, and I could also send e-mails which was “new” back then, but it was still important to write personal letters (snail mail) to different people in many countries.

HJ: In your recent lecture at UMPRUM you said that you wanted to discuss the paradoxes of feminist writing about women artists. How has it changed since 1998 and what are its paradoxes nowadays?

KD: In the talk, I mentioned how Janet Woolf had captured the problem of feminist writing about women artists very beautifully, nearly twenty years ago. She spoke about the ways in which feminism is caught between a politics of interrogation and a politics of correction. Feminists constantly try to correct the absence of women artists by interrogating how their work is discussed. They raise questions about how women artists’ work is received and at the same time try to push research further by offering new readings about their work. But we’re caught, because it seems like the media is always replaying the same questions about women artists as if they have discovered suddenly there was an issue for the first time that they should “now” pay attention to. I call this media approach a constant “taking the temperature” of feminism, is it in? is it out? Is it current? Or is it over? So, in every situation, we feel like we have to rehearse, again, the same initial arguments. It’s like an endless cycle that we’re caught in. First, readers/audiences have to recognize that there is a problem of representation or recognition/of quality or achievement, and if they don’t recognize that there’s a problem, how do we provide evidence to correct this assumption? If they believe there is no problem for women artists “now” because women appear to be currently dominant within their “local” art worlds, then they might want to assert that feminists have nothing to say, or feminism has become redundant because the problem is “over” and the matter solved. But feminist ideas or readings of women artists are far from redundant, they continue to ask quite deep, meaningful questions about practices for women artists, but in this type of conversation the audience/reader is asking us to correct again the picture of culture, to provide new kinds of interrogation. Feminist scholars keep correcting the picture of culture and when they do this, people then say we’ve done it now, this problem is solved. And we have to say, no, the problem’s still there in our collections, in our museums, in our public education system, we’re not away from it, we’re just endlessly doing the same thing, “correcting” the picture.

HJ: Do you feel this problem might be connected to intergenerational issues or the perception that every new wave of feminism sets out anew or has to question or reject ideas of the previous feminist generation?

KD: I’m quite torn between thinking that people still only have very superficial engagement in a series of key questions that define feminism (as above), and at the same time forcing people/publics/audiences to realise that this is a 50-year-old debate and that today the situation has actually changed. Probably what we really have to address now is the problem of “exceptionalism” and the general understanding that there are no longer five or ten women artists who are “exceptions” to women as a sex, and that maybe we have to point to six hundred or several thousand women artists who have had successful careers lasting fifty years producing huge and impressive bodies of work. So, how are we actually going to talk about a new kind of “business-as-usual” which constantly and consistently incorporates their life-long achievements into the history of contemporary art? How are we going to talk about the mass of women artists? Not just the one or two bright exceptions, who are popular with the publicity machine of the art world’s latest exhibition or the key work in a biennale or a single high sale price. This is a larger question about the selective tradition.

HJ: There are a lot more women artists than have not been accounted for in art history or somehow lost. There’s still such a massive gender imbalance.

KD: So how can we manage this – will a politics of correction really address this —‘we have more women artists, let’s have more shows, let’s have more articles by women artists, let’s do more…’—but we’re still not changing anything about the structure of knowledge which produced this situation, we just have more women artists. We’re not really changing anything in art, which was the actual project of feminists, to change the value system. And in more publicity, more interviews, more visibility, we often do not come back to changing the ways in which art works are received and discussed. Stereotypes persist. Even though there are more women artists.

HJ: So you feel that nothing has changed, since the way it has worked in the 70s?

KD: On the contrary, things have changed quite dramatically. But the problem is that now, in the art world, instead of saying that women artists are completely marginal, now there’s a hunger to invest in women artists, to organise special museum programmes to “correct the picture” but not necessarily to reassess criteria for art. Why now, when this argument has been around since the 1970s? So, galleries who in the 70s used to have 10 percent women artists or less have now increased this representation to 30 percent, and this is widespread in the international art world as a new “norm”. You can find these levels of representation whether you go to Tokyo or New York, but if this is now “business-as-usual”, does that mean women artists’ works can only be represented at this level, and has anything changed in how they are discussed in the mainstream, or only the subject of special issues of mainstream magazines or museum shows – because there are plenty of negative stereotypes about women artists’ work evident in art criticism.

This change has happened because the art world itself has massively expanded since the sixties, there are more galleries, more institutions, more art magazines, a greater system overall in scale and in the numbers of people involved. There are more opportunities for more art and more people. It’s only in this expansion of the art world that the number of opportunities for women artists has risen: and this is a well-known sociological trend about the position of women labour force increasing in expanding markets.

I’m asking you whether really, we’ve changed values for art dramatically? Because when you start to look at whether the art world continues to recognize itself as an industry, and how it organizes itself as an industry, has it changed? Women artists are increasingly defining what contemporary art is in and through their art practices in all media. The art world feeds on more “disposable” talent, more diversity, more innovation to enhance its reputation in a globally diverse world. But if you actually look at the real imbalances, for example, how much, really, how much work from Africa is showing in Prague, or how much work from India is showing in Prague, then you start to realize that actually all the rhetoric about diversity or global exchanges is not very profound.

HJ: I would probably argue that neoliberalism and a lack of space that the situation is even worse than it was in the 70s.

KD: Okay, are you’re asking me if there has been some kind of progress in these changes? I’m actually not convinced by a model of change as progress to “equality”, because the key question is “equal to what?”. Feminism is a progressive force but is feminism behind all these changes? I’m starting to question whether that really is the case. Because, you know, there are other larger forces, political, economic and social at work, and if you think about the politics of globalization (an economic construction) and how it’s reflected in the art world, it’s very strange with regard to women. It’s not an equal playing field and it has not been ever. The hierarchies and the systems of dominance are still there, and we need to look really at how and why this change has taken place and its uneven development. We have many versions of feminism in play. We have one dominant story about women’s empowerment, progress, success and achievement, which is “achievement” in a strong, neoliberal world, in which there are many women artists who are doing extremely well financially and economically.

And you can find prominent women who fit in with that model, who are highly successful, from any part of the world today. And then, we have this other version of feminism which is about social rights and social justice and tackling different subjects and value systems or working collectively to produce alternative models of making art and in many cases the two don’t meet because there is not one way of succeeding as an artist or gaining visibility for one’s work.

HJ: I don’t feel that the first model that is looking for exceptionalism, this white, neo-liberal feminism…

KD: No, neoliberal feminism should not be confused with a critique of “white” feminism, it’s deliberately neo-liberal, mobile, dispersed, diasporic, but it is looking for exceptions, it is looking for marginal people, it’s looking for people to promote in exactly the same ways as young male cultural heroes were being promoted in Europe in the 1970s – it is a business model, even when it is marketing “difference”. It’s just contemporary art, not modernism.

Grass roots organisation between artists in small-scale initiatives and building art communities or art scenes in a particular place is something quite different. Perhaps we should think about their rapid commercialisation or museumification?

HJ: Can we talk about concrete challenges for young artists that are interested in working according to feminist principles?

The concrete challenges would be the same. Finding a platform for their work, identifying a peer group, and whether this group was male or female, looking for people to share skills, ideas, work together and initiate things. Artists always see what is possible in terms of range of events, activities, exhibitions, reading groups they want to work with or generate ideas through. Young women artists should try to meet as many people who would be interested or with whom they could share and develop their ideas. That’s the concrete reality of being an artist, I don’t actually think that’s changed.

HJ: Are you talking about autonomy, collaboration and collectivity?

KD: Yes, networks and circles of friends promoting each other… even if those networks weren’t in the same city or from the same art school, because of the internationalism within the art world today, because it is necessary to look internationally. However, that’s not something new in how people operate, that’s what people have been doing for years throughout the 20th century into the 21st.

HJ: Can we discuss art manifestos, especially those in relation to feminism. You collect manifestos and publish them as part of the Feminist-Art-Observatory on KT press’ website. Are they just a performative art form, or are they a political tool?

KD: A lot of these feminist art manifestos were often produced as ephemeral documents: an artist’s statement or even as a press release. Manifestos are a means to promote and present a position. I see manifestos as positional statements. They don’t necessarily hold “true” for many years, but they do represent certain positions at different times. Some of the statements are openly critical of society and of how it’s organized within the art world, and I think it is very interesting to review what these criticisms were and whether they are still valid now. Others of them are more radical statements about the affirmation of particular kinds of women’s subjectivity, both in their present and as a future potential.

I included some very polemical manifestos, for example Michele Wallace’s WSABAL group manifesto (1970), which is her and her artist mother Faith Ringgold’s statement that there should be 50 percent of minorities, of black women artists in every show. It’s a very early statement about the exclusion and marginalisation of black women artists in America from the art world, token figures and how they should regain visibility in the art world.

You can contrast that for example with a Swedish one that I included, which is the FÖRENINGEN JA!/ YES! Association, JÄMLIKHETSAVTAL #1(THE EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES AGREEMENT #1) (2005) which is a contract, a draft contract for equal opportunities policy in every exhibition and in every museum about policy at every level, from the curatorial, managerial, to the cleaners in the museum.

HJ: I think it’s interesting how we arrived to the role of art institutions. If manifestos are a contract as we demand that above mentioned manifestos should be, how can they become a political tool outside of institutions?

KD: Well, the YES! Association one, or even the [Feminist (art) Institution manifesto] (Tereza Stejskalová) Code of Practice (2017) from Tranzit, these are the examples of what could we do, what could we realistically do to implement change. We have come full circle back from radical statements to practical strategies. And to me, that shift from radical statements from the 70s, practical strategies from the 1980s, and in 2018, we could see this as another stage of proposals and organising strategies. And then are we actually doing it on a larger scale, that could have impact on the art world as a whole or are these just echoes of earlier questions? Are they repeating ideas from earlier visions, attempts and experiments to change things. I’m wondering, about this question: how effective will these new attempts be, how much change are we really going to see?

We’ve really been dealing with this problem of sexism in the art world for 50 years, and as individuals we can’t solve it? It’s beyond solving by any one action or a single initiative. Coupled with this, we have to recognise people’s erratic, partial knowledge of feminist debates, or their investments in particular feminist heroes. Those of us who are part of an elite (ie the few who actually research and explore these ideas in some detail) are taking a big risk if they assume that these lines of enquiry that we have known and understood are shared, they are not. They’re clearly not. I’m not going to be critical of any of the recent contemporary developments, I think they’re all great, they are all fine, but I am going to say that there is a dangerous tendency to echo and repeat, whether it is done as a considered linking back to the past or done without any knowledge of previous initiatives given that sometimes people are genuinely unaware.

There is an assumption that we have understood and absorbed Judith Butler and moved on, or that we have understood and absorbed a view of 1970s feminism, and moved on, but I think that’s false. Because people are constantly coming back and seeing completely different things in Judith Butler – and she is still producing new work. Or looking back and seeing completely different things about 1970s feminism, and these are distinct from how we looked back at the 1970s in the 1990s. There is no such thing as a single shared understanding of where feminism is going. Or a simplistic view of feminist politics – in spite of the negative caricatures of its positions, especially by the right. We also have a massive hole in our education programmes which has meant that people are not being taught about the histories of feminist debates consistently – only in the token lecture, guest programme or special optional course. It’s not part of mainstream education and women’s studies/gender theory is under attack, even in the small foothold it has managed to formalise or maintain with University structures. So, the partiality or adoption of small groups of women who could be interested in this kind of thing is happening outside, it is happening in small reading groups, it’s happening in a kind of reinvention of feminism for themselves. That’s where it is now. It’s not in the art school any more. The students’ encounter with feminist theory of any kind is so minimal, a single lecture, one week, or one course on general representation in sexuality, covering everything from critical theory to history of sexuality. It’s presence is still regarded as “too much”, or a some bold gesture but in actuality it is far too little to get to grips with 50 years of debate.

HJ: You have set up a free online feminist art course, in n.paradoxa’s MOOC (https://nparadoxa.com). Do you consider access to feminist education as a part of solution to address these imbalances?

KD: I was trying to tackle the number one problem, access to education and experiment with how we have switched to online as a reference or resource. What feminists have always done was centred in education, self-education and self-help. We know the vehicles we have are small and limited, curating exhibitions, making a publication or editing an art magazine. We continue to put across our ideas. And we keep trying to invent. Feminist curators have endlessly invented new models – not better, not superseding – but different models of how to present feminist ideas and women artists’ works. This is why I think we’re in an endless process. It is not a model of progress, where there’s an end in sight, it’s endless. I think we have to be more conscious about what the content of these models are. Instead of reinventing the wheel, we have to remember all the wonderful interventions that took place before we started working and as we have been working. Because I have deep respect for all these projects and exhibition projects that’ve been organized and that were trying to convey new ways of thinking about these ideas. For example, in Gender Check (MUMOK, 2009) or re-act feminism (Akademie der Kunst, Berlin, 2013), there has been some phenomenal work done in contemporary art. In the big global exhibitions of 2007, WACK!, Global Feminisms, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Gender Battle, there has been incredible work done, but it was only a beginning. If you look at the list of international feminist art exhibitions, there are many precedents of feminist international exchanges since the mid-1970s, with different frameworks, explanations and artists.

HJ: You have been talking about radical and practical solutions which can be understood as a call to re-invent models, to questions the content of these new models… Do you think there’s presently a lack of invention ?

KD: No, no, I think feminism today is very inventive. But I’d just like to make sure that it was a bit better resourced. You know, imaginatively resourced, with historical knowledge of what was done before. That’s what I’ve been trying to push and encourage people to think about. The Feminist-Art-Observatory provides a way of pointing to the possibility for this resource in an information age. Looking back at these fifty years around the world, of different feminist initiatives, this history and legacy is an incredible resource. We need to actually develop different strategies for our age. This doesn’t mean they have to be new, better or more ideal, but they will be different as they will address different needs and perspectives. If anything, we could say that the problem is that we’re caught in a cycle of endless cultural production. If you really want to be a feminist and you want to do something radical, you would stop.

HJ: You would just stop?

KD: Yeah. You just wouldn’t bother. Take time to reflect. Think again.

HJ: Writings of the Polish philosopher Ewa Majewska addresses the idea of weakness, of recognizing slowness as a political strategy. She talks about these strategies as a refusal of capitalist productivity and emphasises importance of expressing emotions and weakness at work and at institutional contexts.

KD: We are caught, you and I, in a cycle of production. I must give a lecture. You must run a magazine. I must do the next book. The problem with these heavily productivist efforts is that it doesn’t give us too much time to step back and reassess. And we do need to step back and reassess, that’s not a politics of weakness, that’s thinking through politics and initiatives in critical ways. I mean, this kind of stepping back is necessary to think again. I’m in that phase right now. I stopped the magazine, I decided not to continue to fuel these tendencies, that are in the air at the moment. If I wanted to, I would have continued with the only international feminist art journal in the world, full of one person profiles of all the women artists who are currently having major touring retrospectives. How wonderful! But my interest was not in producing more publicity material, more grist to the mill! Catalogue essays and retrospectives are the place for this. My academic interest has always been in the relationship between feminist theory and contemporary art in art criticism.

HJ: Talking about this, to conclude, you have produced a new book recently, can you tell us about it?

KD: My new book, co-edited with Agata Jakubowska, is called All-women art spaces in Europe in the long 1970s (Liverpool University Press, 2018). It’s an anthology of eleven essays from different European countries, and it’s about the collective practices of women artists. Either collectively produced work or exhibitions, women’s art spaces, women’s art galleries and temporary exhibition projects set up by women. It looks at the period between 1970 and 1984, and it looks at countries in all regions of Europe, East / West / North/ South, but it only covers ten countries. The book is not a comprehensive survey, but a series of case studies about collective practice in the feminist movement. It’s discussing the problematic of feminist art practice in relationship to the exhibitions of women artists. Most of the essays go through the critical reception of these spaces, the work and the changing aspirations of the women involved in these projects and their goals. It’s a reminder of the history of collective practices by women artists in different European contexts in that period, where the debates in diverse Socialist, post-Dictatorship, liberal and social democracies were very different.

Katy Deepwell is a feminist art critic and academic, based in London and professor at Middlesex University. She is the founder and editor of n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal, published since 1998 to 2018 by KT press. The journal was part of Documenta 12 Magazines Project in 2007. n.paradoxa was an international art magazine which published articles on women artists from around the world. She founded KT press as a feminist publishing company to publish the journal and books on feminist art.

Interview by Hana Janečková

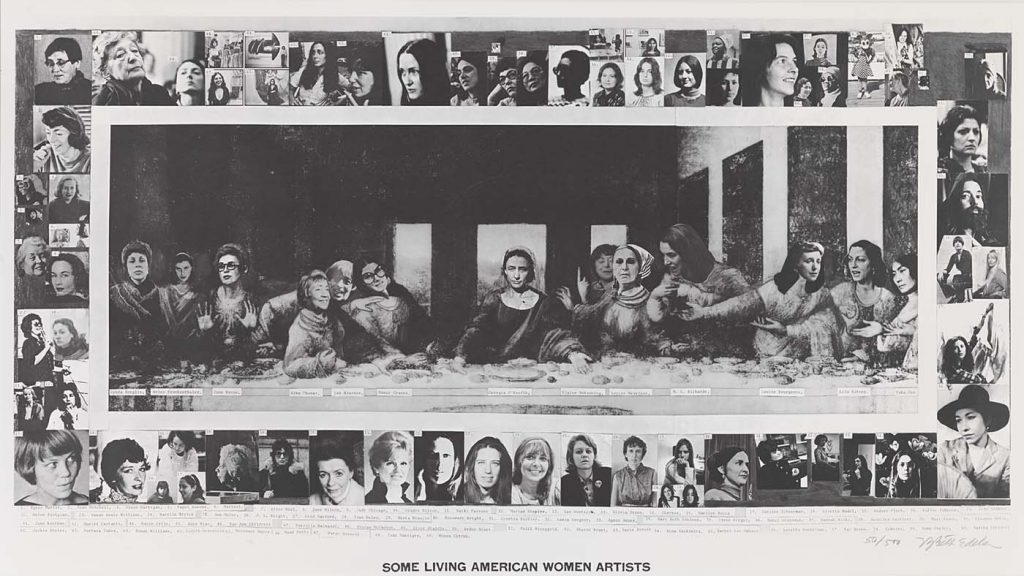

Featured image: Mary Edelson, Last Supper, courtesy of n.paradoxa